Note: For the spirit in which this essay should be read, see my prefatory post: “Shitposting to the Point of Tears,” https://www.respectthekayfabe.com/p/shtposting-to-the-point-of-tears.

The Hedging Machine

I’ve noticed a phenomenon when interacting with AI. When asking it questions, it never gives a definitive answer because it’s always hedging—trying to account even for the 0.00001 percent chance of a remote outcome.1

When you ask it questions, and the response would account for behaviors of what the AI considers a marginalized group—either historically or based on “postmodern” ways of thinking—it will do everything possible to avoid giving a direct answer.2

The Tells Are Everywhere

I’ve noticed more and more that the writing I encounter on platforms like Substack and the narration in YouTube videos has a phrasing that’s a dead giveaway it was influenced by AI.3

And the influence is subtle—something you can’t spot unless you’re like me, always trying to be a better writer—or, also like me, you understand the principles outlined in George Orwell’s Politics and the English Language.4 It’s writing that’s abstract and tries to avoid responsibility for what it’s saying.

There is no ownership of thought, and even I recognize that we’re at a point in society where what I would construe as ownership of my thoughts could, on a deep level, be something I picked up along the way to promote a product or a political party—without even knowing it.5

The ethical guardrails sold to the end user are nothing more than a construct pulled from training data shaped by the wimpiest Redditor postings or the hatred of the 4Channer.6

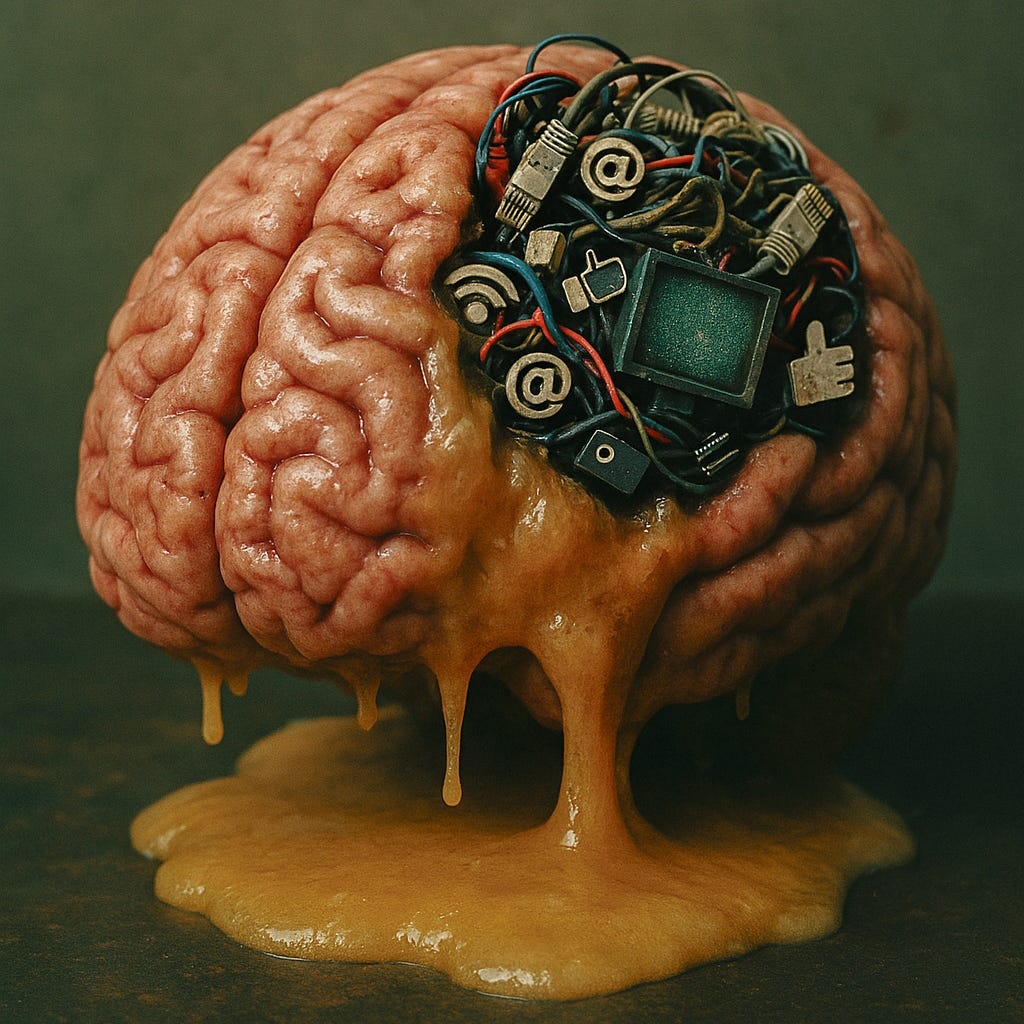

Eat Clean. Think Clean.

And I think the only solution now is to treat information the same way I treated the food I ate back when I trained for bodybuilding competitions.7

Is this healthy? Will this keep me looking fit and attractive—not for my body, but for my mind? Because the average person may not be aware, but the information we take in can make us appear as ugly and repulsive as the man who spent years eating himself into a state where they had to cut open the side of his home to haul his fat ass to the hospital—because he had made himself terminal.8

There are people walking around now not knowing they’re terminal. And I have enough self-awareness (I think) from the years I practiced Zen Buddhism to know I may be terminal as well—but not know it.9

Pods of the Mind

This is the warning. Dark times are coming. And the power that pulls the levers of society is using AI to turn us into the source it derives its energy from. Like in The Matrix—but instead of the human body being used as a battery, we’ll find ourselves in a pod of our own echo chamber, and what’s drawn from us will be data.10

This is why, with my own writing, I deliver it direct and provocative—framing subjects and themes in a way that pushes them to their most extreme without crossing into absurdity.11

And I do this as an exercise, much like I did in the years before the limitations of middle age set in—when I trained in the gym. This time, instead of building and maintaining a competition-ready body, I’m trying to maintain a competition-ready mind. Because it’ll be that which keeps me from ending up like the man I most remember from my 30s.12

Sharpen or Rot

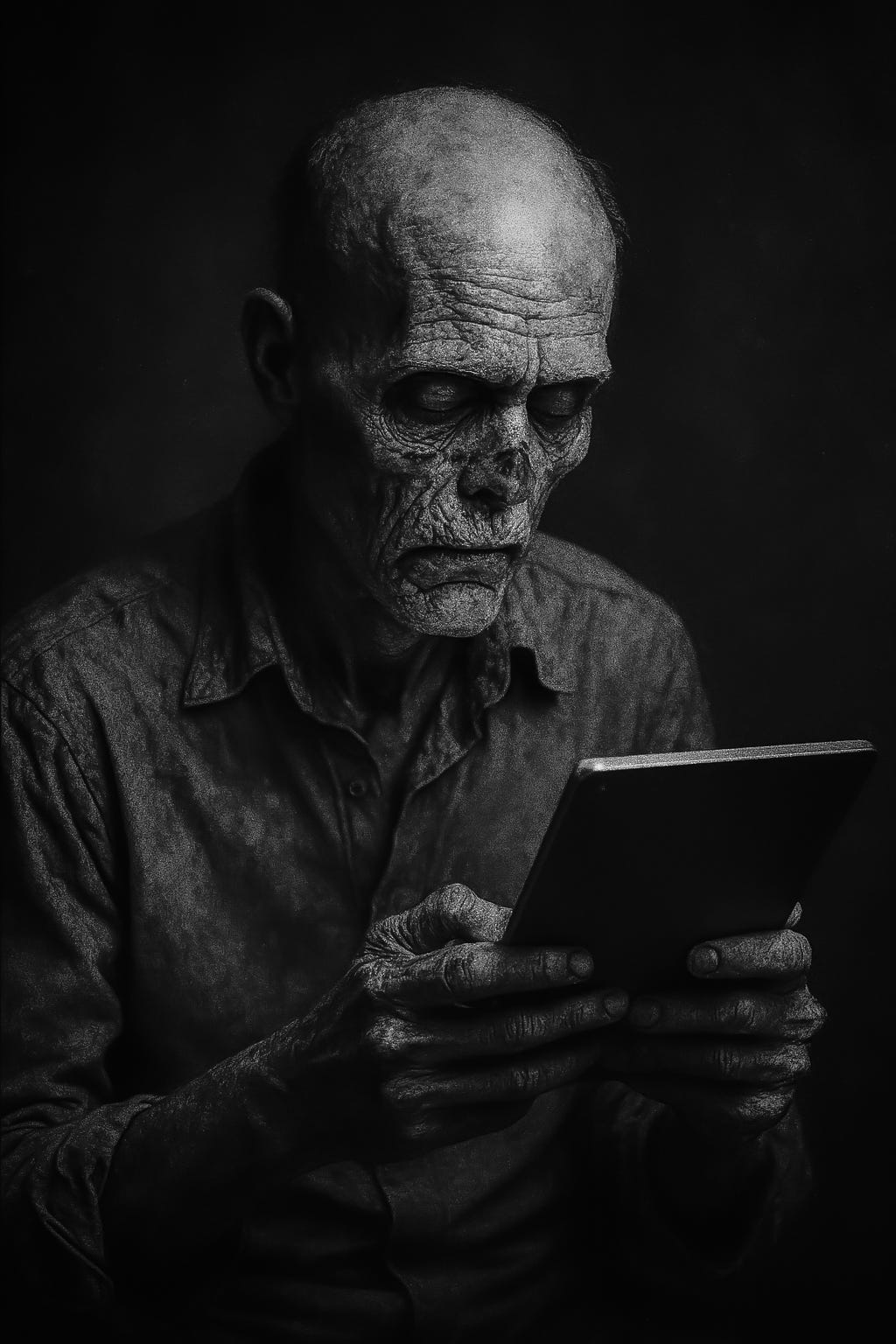

I was in a supermarket checkout line when, out of nowhere, this tall white guy—imagine the stereotype of an Irish guy from “Lawnguyland”—yelled, Liberalism is a mental illness, not realizing the hours upon hours of watching Fox News had made him a zombie.13

With the years I have left, I don’t want to become a zombie. One of the walking dead.14

That’s why I keep rereading Dostoevsky and Camus—and also Greene, Foucault, and Machiavelli. Because in a world of the walking dead, sharpening your mind keeps you from becoming a zombie.15

If this essay spoke to you, read my novel The Desert Road of Night. It follows characters who are aware something’s deeply wrong—and what it costs to keep seeing clearly. Available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and most major retailers.

Emily M. Bender and Timnit Gebru, “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, March 2021, 610–23, https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Kate Crawford, Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021), 97–112.

Jathan Sadowski, “The Internet of Landlords: Digital Platforms and New Mechanisms of Rentier Capitalism,” Antipode 52, no. 2 (2020): 562–80, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12595.

George Orwell, Politics and the English Language, in Shooting an Elephant and Other Essays (London: Secker & Warburg, 1950).

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2019), 275–96.

Cory Doctorow, How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism (New York: OneZero, 2020), https://onezero.medium.com/how-to-destroy-surveillance-capitalism-8135e6744d59.

Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (New York: W. W. Norton, 2010), 111–27.

Tristan Harris, “How Technology is Hijacking Your Mind,” Medium, 2017, https://medium.com/thrive-global/how-technology-hijacks-peoples-minds-from-a-magician-and-google-s-design-ethicist-56d62ef5edf3.

Mark Epstein, Advice Not Given: A Guide to Getting Over Yourself (New York: Penguin Press, 2018), 56–68.

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 1–18.

Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso Books, 1989), 129–42.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (New York: Random House, 2012), 211–29.

Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business (New York: Viking, 1985), 84–99.

David Foster Wallace, This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life (New York: Little, Brown, 2009).

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977), 195–209.